I went to Marseille because a hot girl told me to. Actually, I went to Marseille because like six different hot girls told me to. First it was Mimi, whose expat Londonness and aristocratic eyeliner have always struck me as incredibly authoritative. Then Danielle Carr spent the summer there. Then Megan Nolan. Sophie Kemp told me it was the most magical place she’d ever been. Suddenly it seemed like all of my slightly older, slightly cooler, significantly more successful female friends were going to Marseille; by late July New York was empty of It girls, having dumped them all in the capital of Provence. (Most famously, perhaps, there’s Kaitlin Phillips, who lives in Marseille part-time.)

All of which is to say that going to Marseille in 2024 felt a bit like going to Mexico City in 2020, which I also did. By that I mean: if you live in a currently-gentrifying neighborhood in New York and could reasonably be accused of helping to gentrify it, your friends are all going but your parents probably aren’t. Marseille is the kind of place that’s popular with creative directors and writers who don’t really write, but hasn’t yet filtered into the West Village clean-girl-aesthetic TikTok scene. It’s still “gritty” (whatever that means) and “alternative” (whatever that means), like if Philly was on the Mediterranean. Or so people say.

I went because all of that sounded great to me. But mostly I went because I wanted to go somewhere. I was quitting my job; I was starting grad school. I wanted to live, for a week, like the people I always seem to meet at parties: the ones who stay out until dawn on a Tuesday, who never seem to have work in the morning, who write small-press books and eat alone at the bars of expensive restaurants, who are always either getting back from or leaving for Europe. I suppose what I’m saying is that I wanted to live like rich people. And Marseille is a city where an American can feel rich.

I was only there for five days. My boyfriend had limited time off and we both had a budget. But even with high expectations I was shocked by how much I loved it. I don’t think it’s the best city for every type of traveler, but it turned out to be perfect for me.

“Marseilles isn't a city for tourists. There's nothing to see. Its beauty can't be photographed. It can only be shared.” — Jean-Claude Izzo, Total Chaos

My boyfriend brought a novel by the Marseillais noir writer Jean-Claude Izzo because he believes that vacation reading should be on-theme.1 Though it was objectively quite dissonant to be reading about the blood-soaked streets of a hardscrabble, crime-ridden city while we were sitting on a sun-soaked balcony in one of the wealthiest neighborhoods2 of that same city, drinking Côtes du Rhône and watching the moon rise over the Mediterranean, one line from the Izzo novel rang completely true to our experience: there’s nothing to see!

I mean that in the best way. There aren’t any world-famous museums. The most iconic building is probably a public housing project built by Le Corbusier, which is very cool—it’s supposed to be a gem of modernist architecture, and was the one cultural thing I was disappointed not to make it to—but not the kind of obligation that hangs over your vacation like a death sentence. There’s a pretty church on a hill. They built it in 1853. You can go there, I guess. We did, but only for the view.

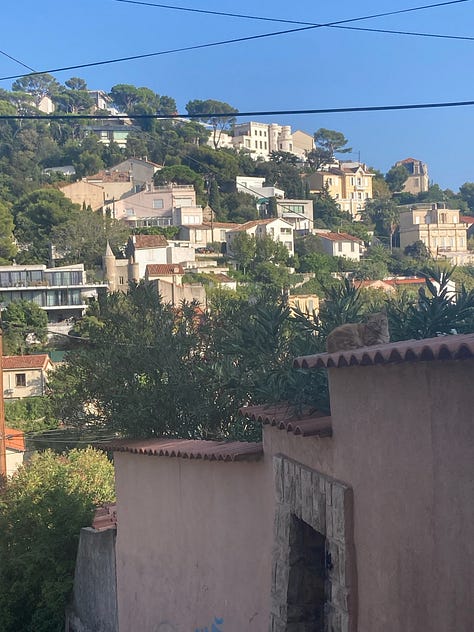

The things to see in Marseille are: the sea. The rocks. The graffiti. The cats. The fig trees. The sunsets. The wine stores and cheese shops and fish markets. The red-tiled roofs. The blue-shuttered windows. The view from the top of any street that is also a staircase.

The things to do in Marseille are: swim in the Mediterranean as often as possible. Clamber over boulders to get the best view of the sunset. Sit in a cafe drinking coffee or rosé and read and watch the light change. Walk through winding, narrow streets3 that slope dramatically uphill. Look for an open boulangerie. Stop in a Corsican grocery store. Drink wine on a cliff. Scrape your knees. Eat seared fish and runny cheese. Sit on a busy city staircase and listen to live jazz and Afrofunk. Smoke a cigarette. Have more coffee. Take the long way home.

Oh, and you have to hike in the Calanques. That’s the only non-negotiable.

On Pastis

Marseille is most itself at sunset. Every night we were there was the kind of perfect summer evening you dream about but hardly ever get in New York—dry warmth, slanting sunlight, peach-and-gold tones everywhere. It was beautiful but almost sort of sad. You could drive yourself crazy worrying about missing the scant half-hour or so when the light fades and blisters and the city walls turn pink. And I did, a couple of times, drive myself crazy, rushing as I was to be nowhere at all.

For my money, there are two perfect ways to spend a sunset in Marseille: either you’re sitting on a rock looking out at the water, maybe with a bottle of wine and a sandwich, or you’re sitting outside a cafe with an aperitif. Which brings me to pastis.

I know it’s gauche to express one’s own dislike of something through disbelief that anyone else could possibly like it. I mean, I love bitter flavors; I roll my eyes when someone says everyone else must be pretending to like Negronis or broccoli rabe. But I can’t shake the feeling that every American who claims to like pastis is, on some level, kidding.

(Apologies to my friends who claim to like pastis.)

Pastis is an anise-flavored liqueur that’s very popular in Provence. You mix it with water and it changes color, which is fun, although the color it changes to is a disgusting opaque milky yellow, so pardon me if that doesn’t add to the appeal. My issue with pastis is that it’s neither bitter (like Suze) nor sweet (like Kir) nor bittersweet (like Aperol, Campari, Chartreuse, Cynar, or any other really great aperitif). It tastes like alcohol. It tastes like unseasoned licorice. It tastes incomplete.

Maybe part of the problem is that I associate pastis so heavily with Jean Rhys. The heroines of her Paris-between-the-wars novels—Quartet, After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie, and Good Morning, Midnight, which I wrote about for Gawker back in 2021—are always ordering it (usually by the brand name Pernod). Look, Jean Rhys is one of my favorite novelists. However, for better and for worse, she does not exactly make drinking look fun. She was a lifelong alcoholic, and her heroines—destitute, dependent, drifting between cheap cafes and horrible boarding houses—are too. Pastis, in my mind, is what you drink in between being cruelly abandoned by your married lover and going home to find that your baby has died.

I drank it exactly once in Marseille, by accident. I tried to order Cassis (a light, local white wine). The waiter misheard my terrible French and brought pastis. I dutifully drank about half of it. Even in Marseille, at sunset, it sucks. Sorry!

Where to eat

Frankly, I have no idea. I went almost nowhere that was on my obsessively-curated Google Maps list. Part of that was poor planning and part of that was intentional Bourdainian spontaneity, which can, of course, be the same thing. Lots of our meals were just bread from the bakery down the street with good butter and cheese, maybe some cured meat or olives or tomato in there too, and they were perfect.

As far as restaurants go, I had a shockingly good vegan lentil salad at Les Lumieres. “Vegan lentil salad” is not a set of words I generally like to see, especially not in France, but there were only three lunch options on the menu and I was craving a vegetable. I was also shocked at how delicious some of the food was at O’Canotier, a bizarrely named brasserie/tabac right off the Corniche Kennedy that we only went to because it was open and near the water (usually bad signs). But the swordfish and gazpacho were tasty, and a dish of stracciatella with cured beef, hazelnuts, and basil oil was genuinely striking.

The only reservation I made in Marseille was at Limmat, and it was one of the best meals of my life. Granted, we hiked the Calanques right before, but I think I would’ve felt that way even if I hadn’t been hungry and exhausted. Limmat serves exactly the kind of food I most love: vegetable-forward dishes with big, punchy flavors that are bright and rich in equal measure. Highlights were a cold bagna cauda that was basically like a super herbaceous, anchovy-flavored whipped cream; a savory ricotta cheesecake with raw and roasted zucchini and lemony pesto; and a fresh goat cheese with stone fruit, roasted carrots, fennel, and griddled cornbread (!), something I’ve never seen in Europe. It could have been dessert. But we got the pavlova, so that was dessert.

Pasta nada

Because we were staying in an AirBnb with a kitchen and a patio table, we decided to cook dinner one night. The original plan was to find a nice piece of fresh fish. This was foiled by every poissonerie near us being closed. It was August and the fishmongers, rightly, were on vacation. You could call this getting Franced. You could also call it the proper order of things.

So I improvised. We had: a pound of pasta, a lump of good butter, some bits of soft cheese, some ends of dry sausage, one zucchini, one tomato, one head of garlic, a small jar of anchovy paste, a small jar of tapenade, and half of two loaves of bread (one baguette, one olive loaf). Plus a bottle of white wine. The AirBnb had olive oil, vinegar, salt, and pepper.

These are the conditions I most love to cook under. I am not a chef; I do not make anything difficult or finicky or complex. The only thing that’s impressive about my cooking is that it tends to taste good, and, secondarily, that I relish the challenge of a bare refrigerator. I really love Dwight Garner’s term “pasta nada”: there is nothing more fun to me than making pasta out of nothing.

And I wanted a spread. So I decided to make two salads, a charcuterie board, and a pasta. The charcuterie board is self-explanatory. The salads were: tomato, chopped, salted, and doused in olive oil; and zucchini, sliced thin and marinated in red wine vinegar, olive oil, tapenade, and black pepper. And the pasta was a true pasta nada. The sauce was just all of the butter we had left, plus all of the jar of anchovy paste. A splash of white wine and lots of pasta water. (You really don’t need many ingredients if you use a lot of a few that taste good.) For a topping, I crisped bits of baguette and thin slices of garlic in olive oil. Hard cheese would have been good; more garlic or onion would have been good; capers or olives would have been good; lemon would have been good. But none of it was necessary. I’d never thought to use butter in an anchovy-based pasta sauce before—my mind always goes straight to olive oil and the South of Italy—but in the South of France? It was perfect.

My boyfriend dutifully called it the best meal of the trip.

Also, Paris

I like Paris more each time I go there. I think it’s because I’ve gotten to know the city just a little bit better—I know what I like and what I don’t, and I no longer feel obligated to go to the Louvre. “Paris tries to get you to do things if you don’t outsmart it,” our friend Chris said. I think that’s exactly right. The best things to do in Paris aren’t really that different from the best things to do in Marseille, except it might be raining.

We flew into Paris and took a train to Marseille because we thought it would be cheaper, which turned out to not really be true. Still, I’m glad to have spent those two nights in Paris. I fell in love with the Hotel de Grandes Ecoles in the Latin Quarter (a neighborhood I didn’t think I particularly liked. I’m always disappointed by the Left Bank, probably because it simply isn’t the Left Bank of Jean Rhys and James Baldwin anymore. But this hotel is just SO good). Now I never want to stay anywhere else. I only found out about it from Ruth Reichl’s newsletter; she wrote favorably about the hotel in a “Paris on a budget” issue of Gourmet magazine back in the aughts.

The other newsletter recommendation I was very happy to have taken? Alison Roman’s. What can I say, that woman gets me. When she said Le Dauphin served the best sole meuniere she’d ever had I immediately made a reservation. And it turned out to be the best sole meuniere I’ve ever had, too, although—it must be noted—I had never ordered sole meuniere before. In New York it is always at least $75 and (I think?) intended for one person. This sole was $65 and fed three people. The meal on the whole wasn’t cheap, but it was definitely cheaper than it would be in New York, and that’s good enough for me.

I think the reason Paris feels cheap isn’t exactly because it is, but because the things we think of as fancy in America are just normal over there. Wine, obviously, is the best example. I never got tired of ordering a glass of Champagne for the price of a house red in Manhattan or allowing the waiter to bring me whatever wine he recommended, because I knew it wouldn’t cost more than $8.

But that’s enough about the ways Paris isn’t like New York. Time to talk about the ways it is.

After dinner one night, during a romantic walk home over one of the islands in the Seine, a rat ran over my foot. Right over my foot. I was wearing sandals. It was so shocking and disgusting I lost my balance and fell right on my ass, cartoonishly, like I’d slipped on a banana peel.4 Two French guys witnessed it and asked if I was alright. “Zat was cray zee. Eee just ran into yoo,” one said.

“I’m fine!” I shouted. “It’s okay! I’m used to it! I’m from New York!”

Ha, ha, ha.

That was the first time I’ve ever said those words. And they only felt true because I was in Paris.

Which I agree with, by the way. That’s why I brought Paris Spleen by Baudelaire and Exposition by Nathalie Leger, neither of which I turned out to like very much. The best thing I read was Kairos by the Berlin writer Jenny Erpenbeck, about an age gap relationship in the last days of East Germany. Rotkäppchen is basically Champagne, right? Anyway, I think Tim chose better than I did. He also brought Another Country, for the South of France sections, and two French NYRB classics: The Child and the River by Henri Bosco and In the Cafe of Lost Youth by Patrick Modiano.

Bompard, south of Endoume. It’s a bit far from the city center (hour walk, 20 minute bus ride) but close to some of the best swimming spots. If you can find a nice, affordable AirBnb or hotel room, I highly recommend staying there.

I love winding, narrow streets so much, and I can’t shut up about it. I probably drove Tim crazy overusing that exact phrase. I am so passionate about winding, narrow streets that I will throw a “bitch fit” (in the words of my friend Tom) if I ever have to walk down a grand boulevard. “I didn’t come to Europe to have to look at a Sunglass Hut,” I believe I once said in Barcelona. I would rather the walk take four times as long, with multiple staircases and weird bridges, than pass a Burger King. Speaking of fast food: Marseille is the first place I’ve seen a Steak and Shake since I left suburban New Jersey. What’s up with that? We saw two.

I do not have a talent for physical comedy, because I can’t control it. But, occasionally, physical comedy happens to me.

You say there was nothing to do, but you met a cat!

thank goodness i was worried this was about the mcnally establishment which i maintain a strong loyalty to